SOME NOTES ON MAINSTREAM PSYCHOLOGY STUDIES ON GENDER DIFFERENCES

There has been discussion in some media articles recently about gender differences between men and women, and whether those differences are inherent or created by society. I’ve tried to summarise below the evidence from psychology about which differences between men and women are consistent across cultures, and which persist or are increased in more gender equal societies.

Below is a link to a journal article by Mac Giolla which takes measurements of personality differences in men and women in several characteristics (agreeableness, contentiousness, openness to new experiences, extraversion, and neuroticism, the latter defined as variability of moods and tendency to experience anxiety, depression, and frustration ) – qualities that are commonly used in psychology descriptions of personality, and are referred to as the “big 5.” If you scroll down to Figure 2 in that article, you’ll see five scatterplots. Each scatterplot has a set of light points (females) and dark points (males) with a line of best fit for both. The vertical axis is the average score for that personality trait in a country, and the horizontal axis is a measure of gender equality for that country. Each dot is the average score for males or females in that country. As you move from left to right, the line of best fit for each gender separates, i.e. the average difference between men and women gets greater, not smaller.

I can’t lift the graphs one at a time, but here is a screen shot of two:

From Mac Giolla 2018.

A paragraph in the results says, “The results indicate that women are typically more worried (Neuroticism), social (Extraversion), inquisitive (Openness), caring (Agreeableness) and responsible (Conscientiousness) than men, and that these differences are larger in more gender equal countries.” (Emphasis added.)

This is the reverse to what most of us have been led to expect over the last 40 years. Most of us have been lead to believe that personality differences are bought about by social conditioning, and if we lived in a more gender equal society, these differences would be reduced. This is not what the data shows.

The discussion shows correlations between higher gender equality in a country and increases in the differences between the sexes in the relevant variable. The “mean” is another word for arithmetic average. The degree of correlation is shown by “r” where zero would mean no correlation and 1 means a perfect correlation.

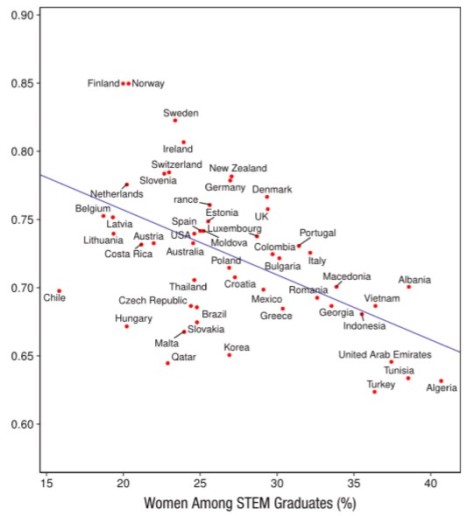

The article by Khazan (2018) includes a scatterplot of women in STEM graduates vs gender equality for several countries.

The more gender equal the society, the fewer women take STEM degrees. Why? She says that one possible reason is that in very gender unequal societies, taking a STEM degree is a sure path to a higher income for girls, whereas “Countries with the highest gender equality tend to be welfare states, [with] a high level of social security… It’s not that gender equality discourages girls from pursuing science. It’s that it allows them not to if they’re not interested.”

The article by Brooks summarises a book by David Schmidt, a professor of evolutionary biology. Schmidt compares cross-country data on gender differences for 28 characteristics. In 20 of the characteristics, the differences between men and women grow bigger in more equal societies. Two characteristics narrow in more equal societies (the tendency to value resources in a mate, which become less pronounced for women in more equal societies, and interest in casual sex, which increases for women in more equal societies, both bringing women closer to men.) Six characteristics don’t change. Brooks says, “Likewise, men score higher than women for the “Dark Triad” traits of Machiavellianism, Narcissism and Psychopathy. Gender equity has the salutary effect of reducing each of these three rather nasty traits, but it does so more for women than for men, resulting in wider sex differences.”

The article by De Bolle looks at personality differences between boys and girls in 23 cultures. The differences are consistent across cultures and emerge around age 12 and converge to adult levels around age 17. The differences emerge around puberty.

Overall, moving to more gender equal societies doesn’t reduce differences between men and women. It increases them. This is hard to understand if differences are produced by ‘the patriarchy’ and social conditioning. On the other hand, it’s easy to understand if there are actual differences between men and women that incline them towards different fields of work or study. More gender equal societies are usually higher income societies, with social safety nets, which means there is a lower cost to doing what you actually want to do.

Now to anticipate some objections. Someone is likely to say, “These are only averages, it makes it sound like all women are more agreeable than all men.” No it doesn’t. Take height (and I’m using height because no one has an ideological position on height, so it’s easy to explain something about graphs without an ideological battle.) We all know that men are on average taller than women. We all know that there is a spread of heights around the average. The next diagram shows the average heights for men and women in the US. Men have an average height of 70 inches with a standard deviation of 4 inches. Women average 65 inches with a standard deviation of 4 inches. Where the two graphs cross at 67-68 inches, there are roughly equal numbers of men and women. But look what happens as you go out to the right or left.

If you have two groups of people where the average measurement is different, and the standard deviation (the degree of spread) is even roughly similar, out at the far left and far right of the graph, there will be a large discrepancies between how many members of each group have (or lack) that quality to a very strong degree. At and above 75 inches, tall men vastly outnumber tall women . At and below 60 inches, short women vastly outnumber short men, by the same margin. This will be similar in anything that can be measured along a scale where the two groups differ on the average and which have the usual bell shaped curve. In the case of height, an eight percent difference in the middle (5 inches over 65) results in differences of about 19:1 in the ratio of tall men (over 75 inches) to tall women. If you ask “who is shorter than 60 inches, women outnumber men by about 19 to 1. (You find the ratio of how many men or women are above 75 measurement by look at the area under the graph to the right of the line at 75 inches. You find the number of men or women shorter than 60 inches by looking at the area under the graph to the left of 60 inches.)

This has implications for other traits where men and women differ at the average. If men are on average more narcissistic than women, the will be many more very narcissistic men than very narcissistic women.

Evolution may have selected for women to be nurturing, since that maximizes the chance of a child surviving. But it means that there will be large differences in the number of women and men who are very nurturing or very indifferent to the needs of others. This is not the same as saying, “all women are more nurturing than all men.” There is a spectrum for both groups , and a difference at the centre means a large difference in the numbers who are very very x (nuturing) or very very not x.

The fact that a difference exists doesn’t tell you why the difference exists. For that you have to go elsewhere. One aspect in which men and women differ is “orientation to things” versus “orientation to people.” Exposure to androgen – a male hormone – in the womb (because of a medical condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia or CAH)) makes girl foetuses become girls with a higher than average orientation to things, so there appears to be a hormonal basis for this difference (Beltz 2011). As Beltz says:

Consistent with hormone effects on interests, females with CAH are considerably more interested than are females without CAH in male-typed toys, leisure activities, and occupations, from childhood through adulthood (reviewed in Blakemore et al., 2009; Cohen-Bendahan et al., 2005); adult females with CAH also engage more in male-typed occupations than do females without CAH (Frisén et al., 2009)

If there are some jobs which call for a certain quality or aptitude, and that characteristic has a different mean (average) for men and women, there will be a large differences in the number of people who have (or lack) that quality to a strong degree (i.e., out at the left and right of the curve). If men score higher on “interest in things” and women score higher in “interest in people,” and there are some jobs which suit people who have that quality to a strong degree, (e.g., engineering vs child care or social work) then men more will be attracted to some jobs and women to others. It’s not a binary, and no sensible person would claim it is. You can (and should) remove obstacles to girls pursuing engineering (if they want) but creating a more gender equal society doesn’t bring about equality of outcomes.

In the case of many jobs, differences in personality attributes between men and women doesn’t really matter. Most jobs don’t require you to have some personality characteristic to an extreme degree. But some do. Engineers tend to be very interested in things, rather than people. Social work, psychology and medicine tend to attract people who are more interested in people rather than things. (You’d hope so, right?) For a discussion of how different personality types are attracted to different university courses see Vedel 2016, or Ali, which is a non-mathematical discussion of Vedel. Law and economics appear to attract people who score low on trustworthiness and concern for others.

To talk as though apparent differences between men and women are “binaries” which we should reject because ‘binaries are wrong’ is to criticise a straw man. Nobody in psychology claims they are binaries. However even when there is a large overlap, there will be an imbalance in the number of men or women exhibiting a characteristic to a high degree. There is no contradiction between saying that men and women can both be narcissistic (or agreeable or tall) and saying that there are gender difference in whether those qualities are exhibited very strongly i.e. i the number of people out at the edge..

Costa, Terracciano and Mcrae (2001) summarize differences in gender across 26 cultures in surveys of 23,000 people.

To sum up: men and women score differently in various aspects of personality. Those differences appear to be consistent across numerous countries and cultures. The qualities involved are not binaries. They are measured along a scale. The differences are greater, not less, in more gender equal societies. This is the opposite of what most of us have believed for the last 40 years. If patriarchal oppression makes girls be more agreeable, contentious etc, it is unclear why the differences between men and women would be greater in more gender equal societies.

There is no contradiction between saying “men and women can both have quality x” and saying that “there are many more men or women who are very very x, or very very not x.” Gender equal societies reduce the disadvantages to women pursuing classes or jobs that actually interest them, so if a job attracts or requires a very strong degree of some quality, the sexes may, and do, select differently.

Richard Snow.

14 Oct 2018

Ali, Aftab, 2016, ‘New study finds link between ‘Big Five’ personality traits and which subject students study at university’ The Conversation, June 21, 2016 https://www.independent.co.uk/student/student-life/Studies/new-study-finds-link-between-big-five-personality-traits-and-which-subject-students-study-at-a6846996.html#r3z-addoor [This article is a discussion of Brooks, Rob, 2016, ‘Gender equity can cause sex differences to grow bigger’]

Beltz, Adriene et al, 2011, ‘Gendered Occupational Interests: Prenatal Androgen Effects on Psychological Orientation to Things Versus People’ Hormones and Behavior Volume 60, Issue 4, September 2011, Pages 313-317 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3166361/

Charles, Maria, and Bradley, Karen. 2009 ‘Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries.’ American Journal of Sociology Vol. 114 pp. 924-976. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19824299

Costa, P Terracciano, A and McCrae, R 2001, ‘Gender Differences in Personality Traits Across Cultures: Robust and Surprising Findings’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 81 pp 322–331

De Bolle, et al, 2015, ‘The Emergence of Sex Differences in Personality Traits in Early Adolescence: A Cross-Sectional, Cross-Cultural Study, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, ‘Volume 108(1), January 2015, p 171–185

Giolla Erik Mac and Kajonius Petri J. 2018 ‘Sex differences in personality are larger in gender equal countries: Replicating and extending a surprising finding’, International Journal of Psychology, 11 September 2018 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12529

Khazan, Olga, 2018, ‘The More Gender Equality, the Fewer Women in STEM’ The Atlantic, Feb 18, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/02/the-more-gender-equality-the-fewer-women-in-stem/553592/

Vedel, Anna, 2016, ‘Big Five personality group differences across academic majors: A systematic review’ Personality and Individual Differences Volume 92, April 2016, Pages 1-10 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886915300921?via%3Dihub

A newspaper article which discusses the topic of gender differences being wider in more gender equal societies, without the maths:

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/patriarchy-paradox-how-equality-reinforces-stereotypes-96cx2bsrp